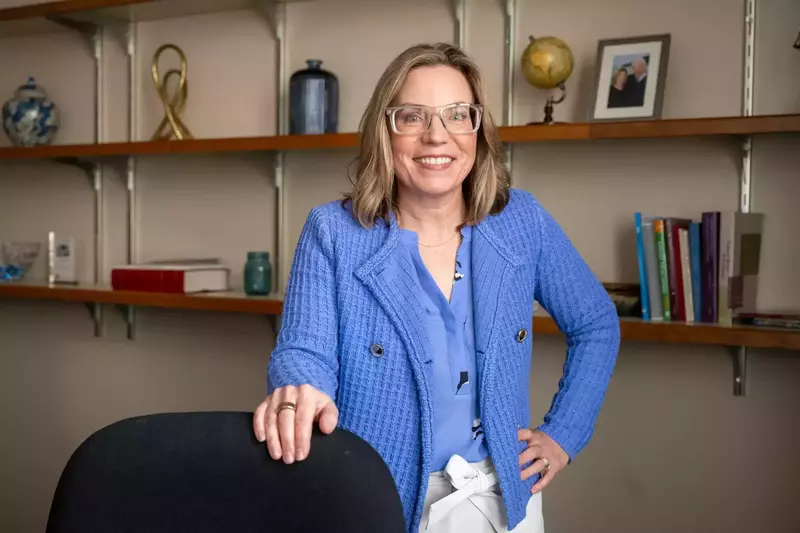

Kristina Swanson is on a mission to build a more inclusive legal community while equipping her students to do important work.

After graduating cum laude from Harvard Law School and clerking, she thrived as a litigation attorney and became known as the go-to brief writer for the most complex cases.

Despite her love of practice and her unquestionable success, she found that the entrenched path to being a successful attorney was not inclusive to many women. “In the law, we tend to measure the success of an attorney about 10 years after graduating from law school,” she explained. “For many people, that puts striving for the highest markers of legal success at the exact same time that family responsibilities begin.

“We put so much pressure on women to not only have it all, but to have it all at the exact same time. That pressure creates barriers to inclusion in the law and makes practicing unnecessarily difficult.”

After her first daughter was born, Swanson, guided by her faith, pressed pause. “My husband had several busy years as a Marine Corps pilot deploying to Iraq. He deserved the chance to pursue the work he wanted, which was in his home state of Indiana.”

Swanson's firm did not have an Indiana office, but someone in her network forwarded her information to Professor James Seckinger, a director of the National Institute for Trial Advocacy and the founder of Notre Dame Law School’s Intensive Trial Advocacy Program.

“Professor Seckinger recognized that my practice experience would be valuable to the students at the Law School, and invited me to teach trial advocacy and deposition skills during the years that we had a young family,” she said. “His support was unusual, and sparked my love of teaching and of Notre Dame.”

Swanson was not done with practice, however. “Practice is my first love,” she explained.

Swanson and her husband put down their roots in Indianapolis, and she built a successful practice. But the teaching spark ignited by Notre Dame never went away. She taught as an adjunct in Indianapolis and eventually made the move to teach legal writing full-time as a visitor at Indiana University.

“ You actually can have it all—but we should normalize not trying to have it all at the exact same time.”

“I reached a point where I accomplished all that I set out to do as an attorney, and thought that the best way I could give back to the profession was by teaching. I also hoped through teaching and writing to begin encouraging changes in the profession to dismantle barriers to women,” she said.

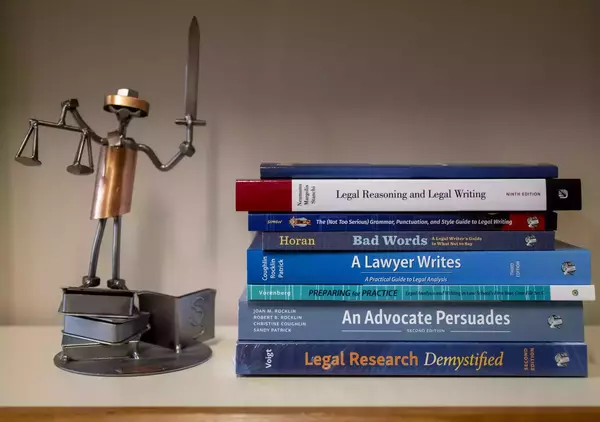

There was never any doubt as to which subject Swanson preferred to teach—legal writing was her clear first choice. Fortunately, she said, not only was legal writing her greatest strength as a practitioner, but it was also having a moment in academia.

Swanson explained that this specialized writing of the legal profession involves communicating complex analyses in a clear and concise manner. “It is used in preparing court filings, of course, but specific legal writing conventions are part of everything lawyers do, from drafting complex agreements to giving client advice.”

Students and legal practitioners were the first to recognize that legal writing is the most foundational skill that they can learn in law school. The nation’s law schools have also caught on and now pursue top attorneys like Swanson as they seek to hire professors with deep practice experience.

An excellent legal education imbues students with an understanding of the art of practice as well as a broad knowledge of the law. When taught well, she said, legal writing combines the law, judicial processes, client relationships, and a healthy mix of language and psychology.

And so, when Swanson heard that Notre Dame planned to hire full-time legal writing faculty, everything seemed to come full circle.

“This job is a dream come true for me. I get to teach about the aspects of legal practice that I most love. I get to help these amazing students prepare for the important work that they will do. Every day, I feel like I am doing exactly what I should be doing.”

Another big reason she feels welcome at Notre Dame is that the Law School never asks its faculty or students to separate law from faith or morality. “We all come from differing faith traditions and sometimes from none, but we all agree that consideration of moral principles is not off-limits in the classroom. In this respect, Notre Dame has built an inclusive culture that not every school has.”

Today, inclusion principles remain Swanson’s chief scholarly interest as well as a guiding star for her approach to teaching legal analysis and writing.

“First,” she said, “I approach every student from a place of humility, understanding that no one starting out in law school knows anything about legal writing—why would they? And then I strive to make clear that my class and office are both welcoming places.”

In her Applied Legal Writing course, for example, when she assigns students to work on a case file that she has prepared based on real cases, she makes certain they know that she welcomes one-on-one mentoring. As a result, she has students in her office every single day of the week. “That,” she said, “is good for me as well as for them.”

If Swanson had just one piece of advice, it might be, “You actually can have it all—but we should normalize not trying to have it all at the exact same time.”

She sees following her faith and prioritizing her family leading to her actually having it all. “My family is thrilled to be a part of the Notre Dame community, and I love my work. I got to do a lot of exciting things in practice and now I have a role in training the next generation of lawyers. Because we can talk about faith, morality, and inclusion at Notre Dame, I believe I am right where I am supposed to be to make a difference for these students and the future of the legal profession.”