Ana Flores-Mireles grew up in Jalisco, Mexico, and assumed she might become a doctor because her aunt worked as one. The job intrigued her. But then her interests changed while watching the movie Jaws.

“I asked my mom, what is that guy’s (character Matt Hooper’s) job? What do you have to do to work with that animal?” Flores-Mireles said, and laughed. “My mom was like, ‘I think he’s a marine biologist.’ So I told her I was going to be a marine biologist, and that really was in my mind for a long time.”

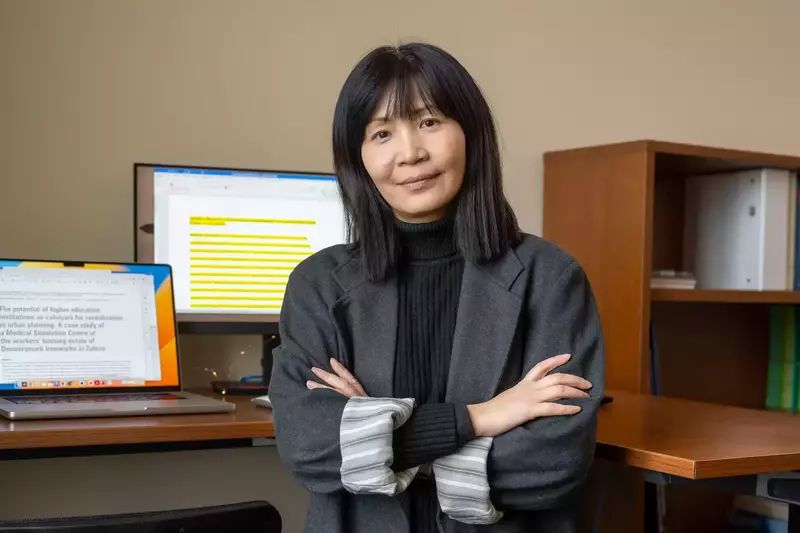

Flores-Mireles, now the Hawk Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Notre Dame, studies microscopic organisms, but her career formed during her study of some of the world’s largest organisms. Now an expert in the understanding of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), she worked with 60,000-pound gray whales as an undergraduate student. In the end, whales, not sharks, led her to her career calling.

During her study of whales, she focused on whether their gene pool was diverse enough to withstand infections, since their long migrations from Alaska to Mexico pass through contaminated water around ports. At that time, she did not relish the requirement to take molecular microbiology and assumed it would be boring.

“But then I became so fascinated; I had to do all of these genetic manipulations, and even do a library of gray whale genes,” Flores-Mireles said. “My molecular microbiology professor said she really thought I was good at this, and she invited me to take a summer to work in environmental microbiology.”

That led to a master’s degree in marine biology, where she observed that microbes seemed to communicate with each other, coordinating behaviors. She decided to understand cell-cell communication between microbes. For that, she completed her doctoral degree in microbiology at Cornell University, focusing on plant pathogens that communicate to infect plants. Her primary area of research was deciphering how the bacteria force the plant to produce a tumor and special food bacteria feast from.

Her training and curiosity led to an environmental approach to the research, looking at the pathogen’s entire environment and how it could affect the plant—and helped her realize early on that she could expand this thinking to apply to humans.

In fact, the concept is not dissimilar to how her research into CAUTIs has evolved. “I realized during grad school that I liked to study human disease, and that the majority of people doing research focus on the pathogen,” Flores-Mireles said. “But my point of view is different; my point of view was as an ecologist.

“I came at the problems with UTIs wondering how the environment in the bladder had changed when a catheter was present; I know when there’s change, or contamination in an environment, that can give microbes the chance to take over.”

She completed her postdoctoral research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, in the lab of Scott Hultgren, the Helen L. Stoever Professor of Molecular Microbiology and the director of the Center for Women’s Infectious Disease Research there. He described Flores-Mireles as one of the most motivated and determined among his 30 postdoctoral fellows to make a breakthrough with regard to host-pathogen interactions and outcomes.

“Ana is absolutely remarkable,” said Hultgren, a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine. “I have had the opportunity to mentor 37 postdoctoral fellows and 33 graduate students, 19 of which have already established their own laboratories as faculty in various institutions. Of those trainees, Ana ranks at the very top. She is an amazing talent . . . she tackles complex problems with precision.”

CAUTIs are among the most common infections in hospitals and nursing homes. While studying the progression of disease, Flores-Mireles noticed that different types of pathogens she was seeing were unable to survive in urine, but survived in the bladder when a catheter is in place. Additionally, the bacteria E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae infect the urinary tract in the absence of urinary catheters, but were not the two most prevalent bacteria in the catheter-associated pathogens.

So she wondered: What’s different in a catheterized bladder that allows other types of bacteria to grow?

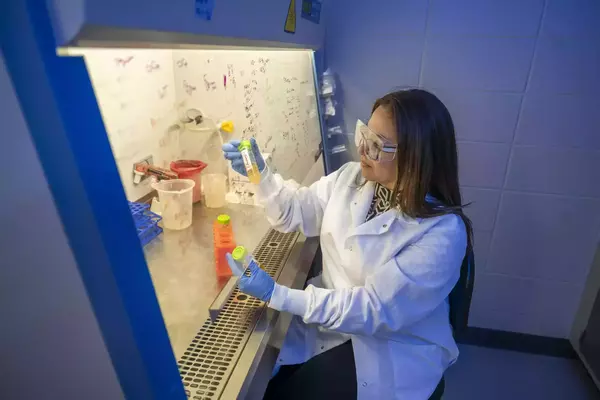

Flores-Mireles discovered that catheters induce severe inflammation, which triggers the recruitment of fibrinogen, a web-like protein found in blood plasma. Fibrinogen forms naturally when our bodies need to heal wounds. In the bladder, when pathogens are present, the fibrinogen becomes both a nutrient source and a platform for microorganisms to stick to each other, creating a “basket” for pathogens to continue growing.

The longer the catheter is in place, the more damage is induced, and the more the fibrinogen comes to the rescue—which creates more niches for the microbes to colonize.

Flores-Mireles used this information to develop a new type of catheter that does not allow the pathogens to stick, and that also minimizes bladder inflammation in general to avoid triggering much fibrinogen production. Flores-Mireles aims to study the catheter in clinical trials soon. She’s also collaborating with Assistant Professor Felipe Santiago-Tirado, her husband, on studies with fungal infections in the bladder.

Her expansive thinking has rubbed off on the graduate students in her lab too. Armando Marrufo, a sixth-year doctoral candidate, said he enjoys the environment that Flores-Mireles sets in her lab overall.

“She is an amazing scientist who is also a very impactful mentor. She takes time out of her very busy schedule to mentor us and teach us extremely valuable skills and tools that we need to become successful researchers,” said Marrufo, who will defend his dissertation in May. “She challenges us to think like researchers to push the boundaries of science. I have learned an incredible amount of knowledge and wisdom from her, which has made me a better scientist and a better person.”

Though Flores-Mireles has seen significant success as a researcher, she acknowledged that she’s had to spend more time “proving” herself as a scientist and a Mexican woman. People in labs have commented on her accent, and some have even made comments of surprise that women work as scientists. Understanding that those comments are a reflection of the other person’s insecurities and ignorance, Flores-Mireles has addressed these struggles with people in her lab as well.

“My lab is very diverse, and I tell students to be proud of what they do,” she said. “I tell them not to take these comments seriously because that person making the comment is only doing damage to themselves—don’t give them the power because of their words.”

Alyssa La Bella, a third-year doctoral student in Flores-Mireles’s lab, appreciates her work as a scientist but also enjoys the lessons she’s taught about working as a woman in science.

“Being able to learn under her mentorship is truly one of the greatest opportunities of my life,” La Bella said. “Ana has always encouraged me to go after big goals, whether it be applying for a prestigious fellowship, submitting papers to high-impact journals, or mastering a new technique in the lab.

“She has made it clear to me that science is no longer a man’s world. I have every right to be where I am today,” La Bella said.

Part of her ability to create a positive lab environment is because Flores-Mireles has felt accepted at Notre Dame since beginning work here in 2018, namely because there are so many female scientists in managerial positions.

“It’s different than when I was doing my Ph.D., and there was only one woman,” Flores-Mireles said. “It’s a very good environment here, and this is a really fun institution where I can collaborate with people that work in all different areas.”

Plus, the awareness that women can be scientists won’t be an issue for her son, who is 7. He can grow up watching both of his parents succeed at the same job, with no preconceived notions.

Though sometimes people in Flores-Mireles’s extended family have slightly bemoaned the fact that she’s not a medical doctor—she had considered it seriously, but ultimately decided that she would not want the burden of what could happen if she made a mistake with a patient—she reminds them that her work with CAUTIs is already contributing to the medical field.

Work that can benefit men. And women . . . but maybe not the shark from Jaws. Of course, she can always pivot.

“I think that’s the fascinating thing: With science, you can have a question and you can answer it in so many different ways,” Flores-Mireles said.